#70People70Years - Theo Burrell

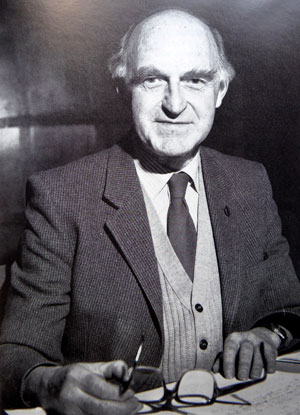

Theo Burrell - former Director and National Park Officer from 1968 to 1985

Theo Burrell - former Director and National Park Officer from 1968 to 1985

Theo Burrell was the chief officer of the Peak Park Planning Board (forerunner to the Peak District National Park Authority) from 1968 to 1985, an important time in the developing organisation’s history. He was born in 1925, died in 1995. He lived in Stoney Middleton with his wife Doreen.

In the early 1970s, the Peak District was England’s only independent national park authority; other National Parks were managed by their county councils, which resulted in a poorer performance record in comparison to the Peak. In 1974, there was a threat that the Peak Park Planning Board could be abolished as part of Local Government Reorganisation, instead, independent national park authorities were established. Theo and leading Board members of the time were pivotal in promoting the Peak's achievements which were highly influential in showcasing what could be done in UK national parks. Theo's own reflections on his retirement in May 1985 are an interesting record of those times.

The following is extracted from the annual report 1984/85:

Thoughts of a retiring National Park Officer [by Theo Burrell]

I was lucky. When I came to the Peak in 1968 I found an authority that had kept its post-war enthusiasm, maintaining high standards and combining innovation with idealism.

National Parks had been fought for up to the 1940s but in 1968 they were a bit out of fashion... except in the Peak.

The Board remained clear on objectives – to preserve and enhance and to provide for the enjoyment of the Peak. Development control standards were embarrassed only by Minister’s quarry decisions in the early 50s. Access agreements were well established; an effective ranger service existed on the northern moors; the Board had begun to acquire and manage small deciduous woodlands; an ex-railway from Ashbourne to Buxton was being converted into a trail; car parks, scenic laybys and lavatories had been provided; a row of disused cottages had been renovated to become Crowden Youth Hostel; there was a new Peak Board caravan site in the grounds of a property called Losehill Hall; and a new information centre at Edale had for a time been a MAFF operations centre as the Peak kept out visitors at the time of a foot and mouth outbreak in 1967. There could have been no doubt of the Board’s dedication to conservation and recreation, but now the idea that the National Park could serve also local interests had been born.

Since then there has been a general widening of the Board's work. They have been busy years, but most enjoyable.

1970 had been European Conservation Year and for the first time we involved continental Europeans, nature conservation - and the press - in the National Park Conference. It was also the year when we acquired Losehill Hall and North Lees Estate, and started the Goyt traffic experiment. We produced our first "glossy" on the work of the Board and our first conservation kit for schools.

In 1971 the Tissington Trail opened and the new Bakewell Information Centre attracted 100,000 visitors in the first year. In 1972 with the support of press and media we toured surrounding cities suggesting a new approach to National Park management, the emphasis being on financial support for traditional farming, a clearer statement of priorities between one area and another, and a more sensible approach to traffic in the Park generally and in the "Routes for People" area south of Buxton and Bakewell in particular. We advocated a new type of National Park Plan. Princess Anne opened our new Study Centre at Losehill Hall. We arranged our first exchange with the US National Parks Service.

1973 was the year when local government reorganisation was much talked about and 1974 was the year when it happened. Our constituent authorities changed but our area remained the same and central government agreed to pay 75% of "accepted National Park expenditure". Other National Parks for the first time employed their own National Park staff and we all started work on National Park Plans. The ranger service was extended to the whole Peak Park; we set up an estates group and employed a volunteers organiser for the first time. We even had a trainee scheme with the idea that there would be future staff demands in our Park, and in others, but later economies meant the job prospects were less and many of these posts have been phased out to match cash limitations and increased work demand of other kinds.

1976 was, as 1985 seems to be, the year of the Public Inquiry. At Old Moor there was ICI's proposed quarry extension into the National Park, a hole a mile long; there was a six lane motorway by-pass proposal for Denton to Hyde that seemed to be heading to go straight through the Peak Park; and there were 30 hectares of slurry lagoon (the size of the built-up area of a Peak village) proposed for upper Coombs Dale. The sad news was that the Secretaries of State for the Environment and Transport did not support the National Park in any of these cases. Following a traffic study initiated by the Peak Board, however, the Transport Minister assured us there wasn’t the traffic demand for a motorway through the National Park – at least during this century. The Environment Minister's Inspector in recommending consent for the slurry lagoon said that Laportes should do research into alternatives to this method of waste disposal. 10 years later a little research into alternatives to present methods of slurry disposal continues. One wonders what will happen when the present dam is filled. Will jobs be put at risk because the firm haven’t found an acceptable means of waste disposal?

The 70s and early 80s have been a period of experiment - traffic management, cycle hire, new bus services, the pioneering of a joint timetable (now taken over by the counties, but probably to be lost with the release of bus service controls), attempts to stop moorland erosion, provision of camping barns, integrated rural development. It was a period too of area projects – no longer jus the ad hoc scheme of car park and toilet, but schemes like the one for the Upper Derwent where (with the exception of a sailing club and some disagreement over considerable planting), Water Authority, Highway Authority, Forestry Commission, National Trust, Peak Board and others worked together on a comprehensive plan for a whole valley. The plans ranged from landscaping to car parks, to park and ride, and to cycle hire with routes to match. We shared the cost, shared the ranger, and carried the plan out with remarkable speed and success.

They have also been years for closer working with the local population. Positively done, this has proved to be the route to success in achieving National Park objectives with local support. Thus our caravan toured 24 villages to get local views when we prepared our structure plan. We improved links with the press, and in 1971 started our own Peak Park News. More extensive design guides (and a lot of negotiation) made more clear what was needed to produce proposals acceptable on development control, and planning refusals were thus kept low (approximately one in five only). Annual parish meetings were arranged and a lot of special ones to develop conservation area proposals with the villagers themselves. Work by Board and other Councils began with the Development Commission to create new jobs. Housing Associations were encouraged to provide low rental housing for local needs. Farm tourism initiatives in Staffordshire Moorlands were encouraged and assisted. We helped develop new ways to make good use of historic buildings. Most ambitious of all in recent years has been the development with two villages of radically different grant systems as an integrated rural development experiment, now more widely known as IRD.

Area plans, IRD and other grassroots working combined with a much wider context. The Peak had won its European Diploma in 1966 in the time of John Foster, my predecessor, but it had to report on work every year since and every 5 years a close inspection is carried out. We are proud to say we still have that Diploma. In 1977 we started European Conferences of our own at Losehill Hall specialising, not in the wilderness type of National Park, but in the Western European husbanded kind. Those conferences now are a successful annual event.

The Peak has also been a member of the European Federation of Nature and National Parks from its beginning in 1973 and, as reported elsewhere, the Federation held its most important conference yet in the Peak last September (see page 37). The reader may sense my own enthusiasm for things European and I shall remain a member of the Federation Council in my retirement.

The National Park emphasis must now be on good land management. Farm Grant Consultation helped greatly, IRD has helped, and the acquisition of Eastern Moors, Roaches and North Lees all present opportunities for just the right balance between conservation, recreation and farming. To support this approach elsewhere it is hoped central government will find the means for different government departments to share common objectives, including a true commitment to the objectives of the National Park. Land management decisions depend on grants and tax concessions; getting that right could in the end be better than unwieldy controls. If that is not done, however, there will be more and more pressure for tougher controls.

The time is now right for National Park work. There was strong public reaction when the Secretary of State for the Environment attempted to water down the Park’s Structure Plan seven years ago. Since then public support for National Parks has grown greatly. The number of volunteers on conservation and ranger work, the increase in press coverage on environmental matters, the great number of people who come to Losehill Hall, all demonstrate a desire, as never before, for conservation. If in doubt, read the Chapter "Who Cares?" in last year's report.

Thanks to a world wide movement outside, National Parks are no longer unfashionable. Thanks to the enthusiasm of the Board itself, we have the skills, but we still lack the resources.

Achievements depend on ideas based on a fair assessment and quite a bit of work. But they also depend on morale as the spur. I was lucky. I had an enthusiastic employer that stuck to its principles, Chairmen who wanted effective initiatives to be taken to make the National Park idea work in practical ways, and I had a staff without equal. All shared a common concern for an area with a tradition worth keeping and scenery worth enjoying.

It is a nice touch that my successor is a son of the John Dower whose National Park objectives were accepted in the 40s, defended from the 50s, and perhaps will only be securely achieved in the 80s and 90s. I wish Michael Dower well.*”

* Michael Dower became the National Park Officer on 1 July 1985.

This 'Appreciation by John Beadle – Chairman of the Board' followed on from Theo Burrell's reflections in the annual report 1984/85:

The Peak District National Park without Theo Burrell at its helm will take a lot of getting used to. Not because he has been a National Park Officer who has hogged the limelight – he is quite the opposite – but because he has always been there supporting, urging, encouraging a first-class staff to give that bit extra.

The Peak District National Park has a reputation as being the most progressive of the ten established in England and Wales. It has pioneered important schemes and initiatives and much of the success must go to Theo Burrell.

During his 16 years with the Board - first as Director and as National Park Officer since 1974 - the Park has achieved so many successes. The continued award of the Council of Europe Diploma, the acquisition of the former railway tracks to establish the well-used Tissington Trail, High Peak and Monsal Trails, the opening of Losehill Hall as a National Park Study Centre, the purchase of the Roaches and the Eastern Moors, the highly acclaimed IRD experiment in Monyash and Longnor are but a few of the successes achieved under Theo's guidance.

Theo has not confined his activities to just the boundaries of the Peak Park. He has been a powerful influence wherever National Park matters are discussed. On the ACC National Parks Committee, where he served as an Advisor, at meetings with the Countryside Commission, at National Park conferences, his contributions are always listened to with respect - his knowledge is there for everyone to tap.

Nor have his interests been confined only to this country. He played a major role in bringing the differing factions in European conservation organisations together in the strengthened European Federation of Nature and National Parks. He gave positive support to the organisation of European Conferences at Losehill Hall and through his activities the Peak Park has become known throughout Europe and, indeed, worldwide.

Though national and international matters are time-consuming, they have not prevented Theo from striving to improve the Board’s image where it was perhaps most in need - with the local population in the National Park area. I think that the rapport established between the Board and the local population under Theo’s guidance must rank as one of his most important achievements.

Contact with Parish Councils in particular has improved so much that many who previously opposed the Board and its activities now see themselves as part of its concept.

Theo would be the first to admit that he has been fortunate to have had the opportunity of spending the last 16 years of his career in such an interesting and challenging post.

Retirement will not end his interest in the Peak District National Park. In fact, it will allow him a little more time to spread his ‘gospel’ in fresh fields. He will be able to use his knowledge and experience to benefit the administration of our countryside.

I know that all members of the Board and, indeed, the many former members too, will want to join with me in thanking Theo for his advice, guidance and friendship he has given over the years. We hope these friendships will not end with his retirement.

May Theo and Doreen [Theo's wife] be blessed with many years of happy, healthy retirement.

Back to 70 People 70 Years.